In studies of the black freedom struggle, there is a tendency to think of each movement in that struggle as a separate and distinct entity. While each phase in the struggle for black liberation has its own history, the black struggle for liberation is not over until the African American people free. Today, 350 years after the first slaves landed in Jamestown; 150 years after the Civil War ended, 61 years after the Supreme Court outlawed segregation, 50 after passage of the landmark Voting Rights Act, and 47 years after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., blacks are still receiving an inadequate education, face police violence, high levels of unemployment, low-incomes, poverty and die prematurely. They are still living in neighborhoods characterized by bad housing, blighted surroundings, food deserts, supportive service swamps, and crime.

Blacks are not free. The black liberation movement is thus a continuum of struggles, where each discrete movements sets the stage and makes possible the next round in the liberation movement. Accordingly, the defeat of slavery was a prerequisite for the battle against Jim Crow Racism, while the legal battles of the thirties and forties made possible the Civil Rights Movement of the fifties and sixties; and these struggles set the stage for the battle against neoliberal capitalism, structural racism and thick injustice. In this blog, I use a theoretical framework based on three interactive concepts: freedom, black positionality in the economy, and black underdevelopment. The thesis is that black subordination in the American hierarchy is based on the interplay of their three factors, operating within the context of structural racism and thick injustice.

Freedom

Freedom is one of those shadowy terms that needs to be carefully defined. In a 2005 report to the U.N., Kofi Annan, then Secretary- General, conceptualized the goals of the Millennium Declaration as the larger freedom; a concept that included food security, social justice, education, work, social well-being, and life without fear or want. Annan’s use of the phrase—in larger freedom—suggest that freedom is a duality composed of two dimensions—smaller and larger freedoms. I argue that the smaller freedom refers to political and democratic rights, including free speech, spatial mobility, gender equality, Gay Rights, and equal treatment under the law, including the right to vote. The larger freedom refers to the right to a living wage; good, affordable housing; quality education; food security; social security, physical, social and mental well-being, and the right to live in a healthy neighborhood without fear of crime and violence. These two dimensions of freedom are interactive, with the smaller freedom being a requisite for obtaining the larger freedom, although securement of the smaller freedom does not automatically mean people will obtain their larger freedom. Only when a people possess both the smaller and larger freedoms are they truly free or liberated.

Positionality of blacks in the Economy

The United States is a hierarchical society, and it is the location and role of blacks in the economy determines their life course, chances and outcomes, and it defines their social relations to other socio-racial groups in society. This positionality of blacks at the bottom rung of the socioeconomic order is the foundation upon which their subordinate status in the United States is based. Within this scheme of conceptualization, blacks were brought to America to work as slaves in country’s most strategic industry—the cotton industry. They were situated at the bottom of the socio-economic order during the slave epoch, and they have been there ever since.

Black Underdevelopment

The concept of black underdevelopment was developed by Walter Rodney, Manning Marable and Clyde Woods. It refers to the brutal and systematic effort to keep blacks powerless and under-educated and to keep their communities weak with limited resources and a fragile organizational and institutional social infrastructure. The goal is to keep blacks from acquiring the critical consciousness, sociopolitical collective efficacy, and resource base needed to win their freedom. Manning Marable, for example, argued that the underdevelopment of African Americans was a requisite for the development of the U.S. political economy.

Using this framework, I will explore the black struggle during four periods in American history. Before proceeding, I want to acknowledge that determining historical periods is a tricky business; in my determination of these four periods, I sought to capture the prime socioeconomic forces driving the development of the United States over time, and locate the black struggle within that moment. These periods are (1) The Slave Epoch [1619 to 1865=246 years]; the Industrializing Age (1866 – 1899 = 33 Years); the Urban Age (1900 – 1950=50 years); and the Age of Neoliberalism (1951-2015=64 years).

The Slave Epoch (1620 -1865)

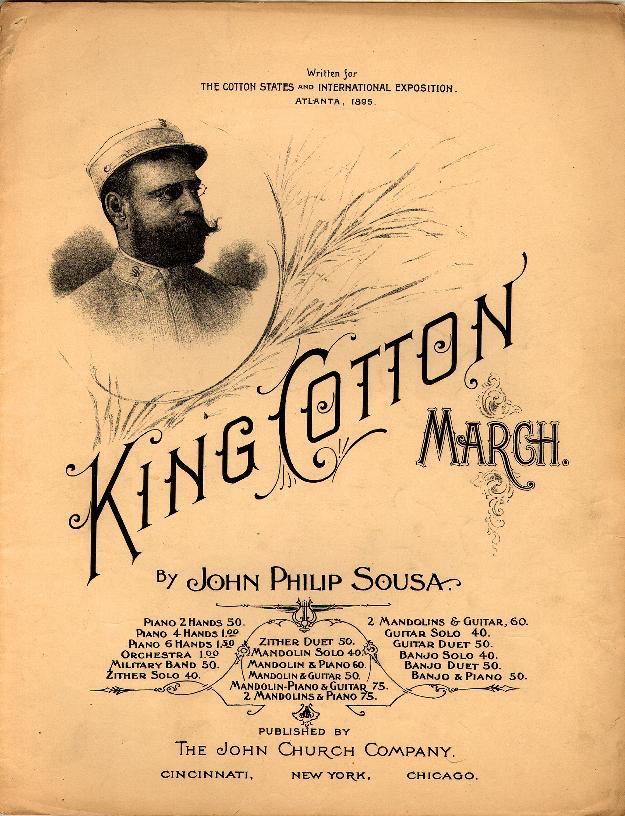

Most people would agree that slavery was a ruthless, mean-spirited abomination. Yet, the system lasted for over 240 years, and it took the bloodiest war in the nation’s history to end. This raises the question, how could something so bad, last for so long? To answer this question, the slave system needs to be situated in the cotton industry and the rise of the textile industries. Cotton was big business, and black slaves were an indispensable and irreplaceable source of labor for that industry. In the 1830s and 1840s, cotton anchored the nation’s political economy and was the generator of untold wealth.

Cotton was King. It was the crucial raw material for the textile industry, and an economic multiplier that produced a large supply chain, composed of a network of companies involved in the production, distribution and retailing of products directly and indirectly related to cotton. Here, we are talking about insurance companies, the shipping industry, ship building, sail making, the clothing industry, along with the manufacture, distribution and retail of guns and ammunition. King Cotton was the leading national export from 1803 to 1937, fostered trade between U.S. and Europe, catalyzed the territorial expansion of the Old Southwest; animated the textile industry and the American Industrial Revolution.

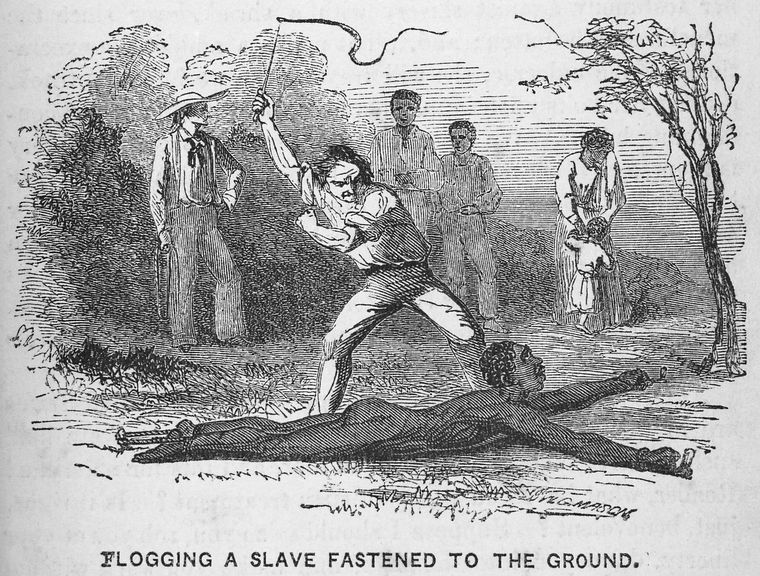

Cotton was King… And this explains why slavery lasted for 245 years. This brings us back to the question of slavery. Black slaves were an indispensable and irreplaceable source of labor. Without them, there would be no cotton industry. Slavery was a requirement for the cotton industry; and the slavery lasted until it became an obsolete of labor, and even then, it took a war to end it. This raises the theoretical question: How could this brutal slave system be sustained over time? For slavery to endure, it was necessary to brutally and systematically underdevelop black people. Black underdevelopment was an ongoing process, not an event. It consisted of efforts to wipe away their African culture, language, traditions and religions. Underdevelopment meant breaking up families apart, raping women, and establishing dependency on the plantation owner. It meant banning education and learning; thwarting the building of organizations and institutions, and it meant creating a brutal system of repression based on terrorism and brutal oppression.

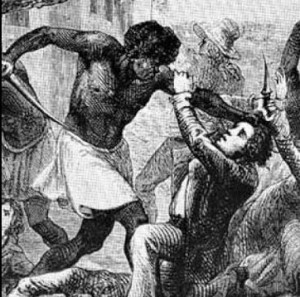

Still blacks fought back, and struggle became imbued within the black experience; it was fused with black values, beliefs and traditions. The plantation became a contested territory. Black slaves were a troublesome property, who created a multiplicity of ways to fight back: they built the slave community; they learned to read and write; invented the Spirituals, both as a new form of music and as a talking drum to communicate with each other; they sabotaged, killed planters, engaged in armed insurrection, and they work Masks of Deceit, which hide their true feelings and desires; produced and engaged in armed insurrection.

And blacks ran away. Escape from slavery was a form of resistance and struggle. This is where the Underground Railroad comes in. Escape from slave system would have been impossible without the support of hundreds of people who put themselves in harm’s way by collaborating with “fugitive” slaves—providing them with encouragement, information, food, money, transportation, meeting places, safe houses and assistance on their journey from the plantation to a liberated zone—where they could recreate their lives and find a life path, which they chose.

The Industrializing Age (1866-1899)

In 1865, the Civil War ended slavery and ushered in a new era in American history. In this moment, the epicenter of structural racism and thick injustice remained in the South, but the focal point of struggle now centered on the battle over land ownership. In many ways this was the most decisive moment in U.S. history. At this critical junction, the United States had a choice: turn over the land belonging to the members of the Confederacy to blacks and provide them with the resources and technical assistance to become the new captains of the cotton industry. Or, allow the former members of the confederacy to regain control over the land, regain political power and reestablish hegemony over the South.

Let me the Choice in context. When the war ended, blacks understood the only way for them to avoid subjugation by racist whites was to own land and obtain the resources to farm it. They also knew that to sustain freedom, they would have to build schools, colleges, institutions, organizations and associations. If they controlled land in the South and built interactive relationships with urban blacks, they could obtain freedom.

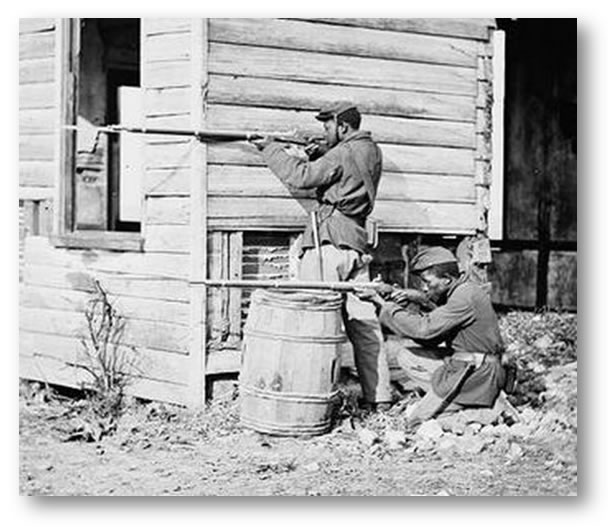

Blacks had every reason to believe that northern white political leadership would support them. The Confederacy had launched the bloodiest war in American history. Over 700,000 Americans died in that war, which is more causalities than all the U.S. wars combined. Blacks, on the other hand, fought and died for the union. About 179,000 blacks, comprising 10% of the Union troops, fought in the war, with about 40,000 dying. So, that was the Choice. Do you give the lands to blacks who toiled it for 246 years and fought and died at your side; or do you give it back to the confederate?

Northern politicians and industrialist were clear. Cotton was still an important component of the southern economy, and these leaders wanted to reconstruct the South under white leadership and control, and this meant returning the confiscated land to their confederate owners and recreating the former slaves as a semi-free peasantry tied to white owned land. To make this system work, a new method of social control had to be established.

During his presidency, Andrew Johnson ordered the return of all land under federal control to its previous owners. The Freedman’s Bureau, then, informed blacks on these lands that they could either sign labor contracts with the planters or be evicted. The army troops would forcibly remove those who refused or resisted. Through these and other means, whites from the old Confederacy were able to regain control over the agricultural lands and reestablish their political power.

Without land or money, most blacks became sharecroppers and tenant framers. Under this system, black families would rent small plots of land, or shares, to work themselves. In return, they would give a portion of their crop to the landowner at the end of the year. The situation of tenant farmers was similar to sharecroppers, but they had the option to use cash or a combination of cash and crops to rent the land.

The sharecropping and tenant system was based anchored by a debt system. The landowner would provide the sharecropper with tools and other supplies, which would be deducted from their share of crops at harvest. Concurrently, sharecroppers and tenants developed relations with local merchant, whom they purchased goods on credit. With owners and merchants keeping the books, blacks found themselves trapped in a system of perpetual debt that kept them tied to the land.

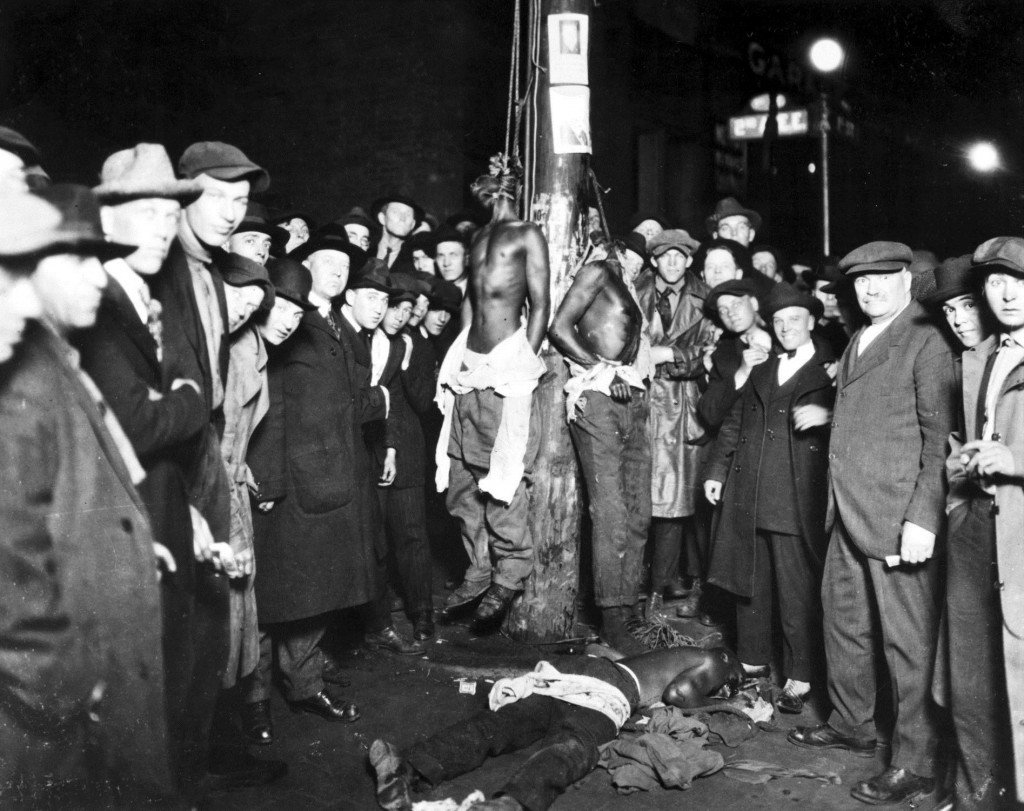

During this period, some blacks acquired land and become independent farmers, but the vast majority of African Americans were sharecroppers. By 1870, only about 30,000 blacks in the South owned land compared with four million others who did not. To maintain control over blacks, whites not only underdeveloped their community, but also the used disenfranchisement, lynching, random acts of violence and the establishment of a rigid system of Jim Crow racial segregation.

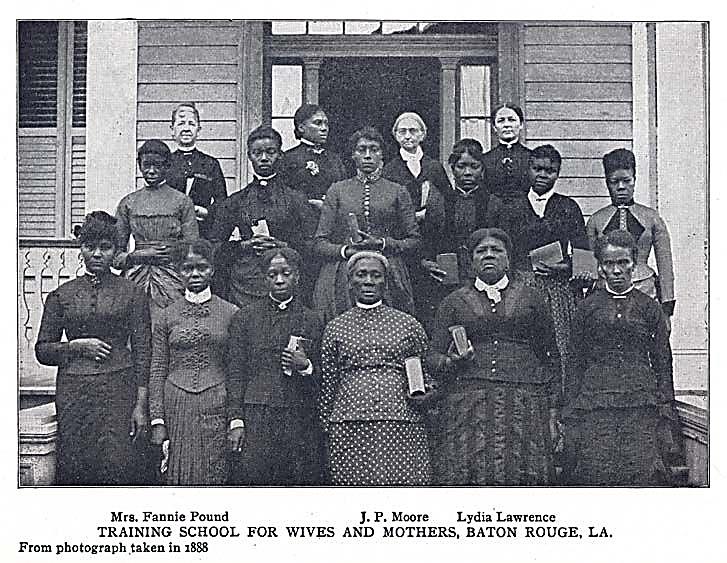

This was the black nadir. Still, African Americans resisted and fought back. On multiple fronts, they pushed back against the underdevelopment of their community. Blacks lost the critical struggle to gain control over the land, but they nevertheless built a strong social infrastructure during the 35 year period between 1865 and 1900. During this period, they build schools, colleges, and churches; they produced a critical mass of preachers, doctors, lawyers, farm owners, business persons, urban workers, and teachers, along with a core of artists, musicians, poets. Most critically, by the turn of the century, Black America had produced a core of radical black scholars and thinkers who were formulating a strategy for moving the race forward.

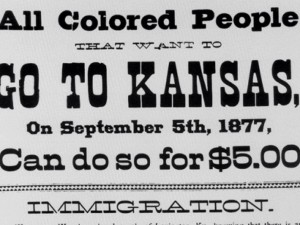

One final note, during this period, blacks continued to use moving or migration as a form of struggle. The black exodusters moved to Kansas, while other African Americans headed to Oklahoma, while still others left for cities in the South and North. As these African Americans left the South, I am sure they used an interactive network of people, supports, meeting places, safe havens to help them make that journey from the rural south to another place, where they could be build a better life for themselves and their families. During the Industrializing Age, although blacks lost the crucial struggle, they still won significant victories. Still, the winds of change were blowing.

On the eve of the 20th century, the black masses were trapped in the most technologically backward sector of the economy, while industrialism was triumphing and the United States was about to become an urban nation. This was both a low and high point in the struggle of African Americans. At one level, they were faced with an intensification of violence and exploitation in the rural South, while on the other hand, a new black leadership and agenda for change was emerging.

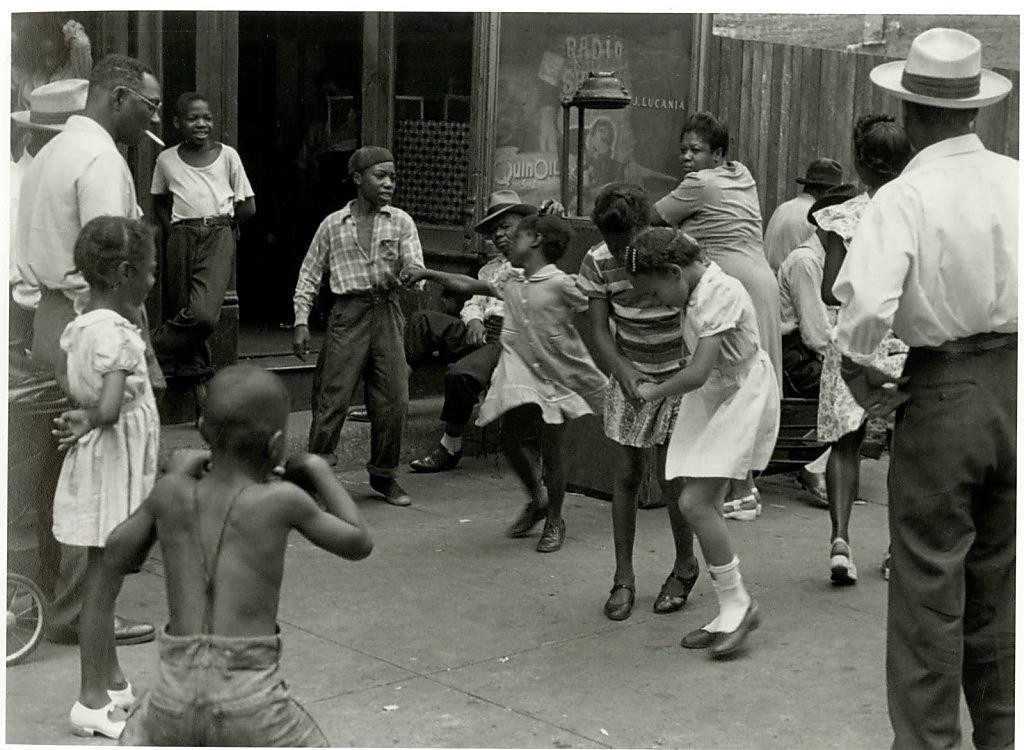

The Urban Age [1900 – 1950]

The first half of the 20th century represented a transitional period in which African Americans would be transformed from urban to a rural people. When the century started, blacks were still a peasantry with about 83% of the population working on farms. This radically changed over the next 50 years. By midcentury, African Americans were now an urban people, with over 60% of the population living in cities. The community was dominated by an industrial proletariat and a small cadre of white-collar and professional service workers. The city was the black people’s land.

Blacks continued to fight against the evils of the debt peonage, violence and the exploitation of black farmers, but the focal point of struggle shifted to the cities, which was now the epicenter of racism and social class inequality. The growth of the black urban community and the transformation of cities into dynamic cultural centers of black life transformed the movement. The black struggle because a national movement that was headquartered in cities. In this context, northern cities became a liberated zone, where the most radical segments of the movement were located. Between 1900 and 1950, the constant inflow of blacks from the rural countryside to the cities became a critical aspect of the black struggle. This constant inflow of people infused the movement with an animating force that expanded the black community and energized the freedom struggle.

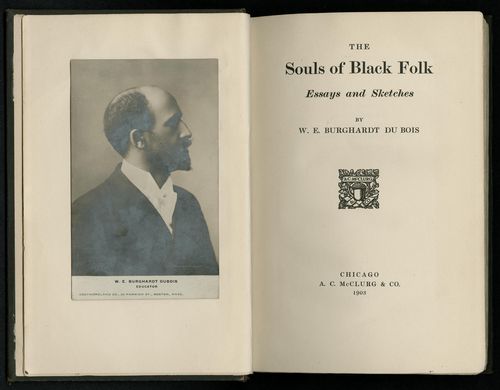

At any rate, publication of the Souls of Black Folks in 1903 by W.E.B. DuBois was a clarion call to action for black America. In the opening paragraph of this classic DuBois declared that the problem of the 20th century would be the problem of the colorline. Two years later, he and other black radicals founded the Niagara Movement. This movement not only signified the metamorphosis of black struggle into a national movement headquartered in cities, but also it forged an agenda of struggle that blacks followed over the next 65 years. In its Declaration of Principles, the Niagara Movement called for the right to vote, equal protection under the law, and equal access to employment, health, decent housing, education and the right to protect and agitate for freedom. The radicals believed that black economic progress and other advances could not be sustained without being anchored by their civil rights.

Following the Niagara Movement, blacks built a plethora of national and local organizations to guide their nascent movement. For example, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was founded in 1909; the Urban League in 1910; the United Negro Improvement Association in 1914; the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915; the Nation of Islam in 1930, and in 1941, and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in 1941. Most critically, these institutions were part of the social infrastructure of the black institutional ghetto. During the urban age, the institutional ghetto anchored the black community and functioned as a platform for struggle against Jim Crow racism. The Ghetto social superstructure consisted of colleges, hospitals, banks, churches, institutions and associational organizations. The Ghetto, then, was a liberated zone from which the freedom movement operated.

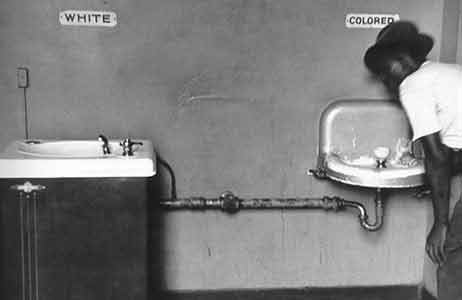

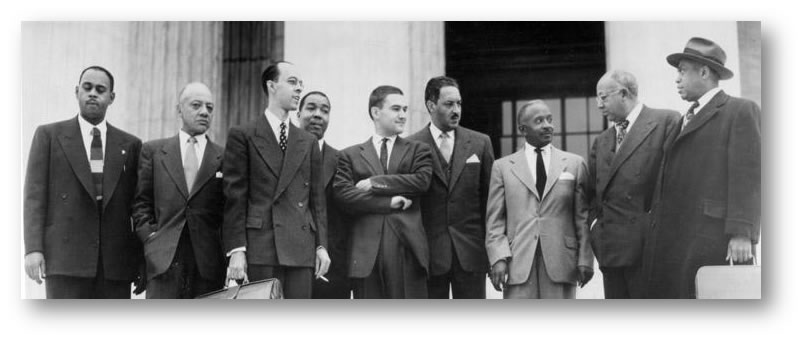

During this period, blacks engaged in intense struggles on multiple fronts; however, the most strategic struggle in this moment was the legal battle. The goal was to demolish the legal foundation upon which Jim Crow stood, while simultaneously enacting public policies that attacked the system frontally.

Black lawyers were the frontline solders in this legal warfare, and the U.S. Supreme Court was the coliseum where the combatants fought. The legal teams won victory and victory on racial issues dealing with travel, employment, and housing; and these Court rulings dismantled state support of practices that violated the principle of equal rights and access to opportunity.

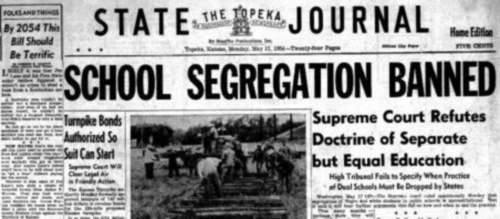

The foundation of the Jim Crow racism, however, was rooted in the “separate-but-equal’ doctrine, established in the 1896, Plessey v. Ferguson decision. If the “separate-but-equal” principle could be defeated on the educational front, the entire Jim Crow system would collapse.

The lawyers argued that separate black schools were not equal to white schools in quality or kind. In 1938, the first victory came when the Supreme Court ruled that the out-of-state-scholarships, provided by certain states for black graduate students, violated the “separate-but-equal” principle, if those same states had graduate schools for white students.

Then, in 1948, the second major victory came when the Court ruled that the Oklahoma Law School must admit a student, which they had rejected based on color, because the State had no black law schools. The third big victory came in a June 1950 Court decision. The Court ruled that the University of Texas had to admit the students because the state’s all-black law school was inferior to the white one. This victory set the stage for the final showdown. In 1954, the Supreme Court announced its landmark decision in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which declared that there is no such thing as separate-but-equal. The ruling destroy the legal foundation upon which Jim Crow racism was built, setting the stage for African Americans to storm the fort and demolish the system.

There are two issues I want to discuss before move on to the next and final epoch. Although making great strides during this period, the black struggle nevertheless suffered a devastating setback. Robert C. Weaver, the black scholar, believed that a racist dual labor market kept African Americans tied to the lowest paying and most obsolete jobs in the economy. This positionality, Weaver believed, made blacks vulnerable, especially in an epoch when the economy was rapidly changing and technology was exploding.

Toward this end, he called for a national policy of “full employment,” which was designed as an alternative to welfare and a method to ensure that everyone who wanted to work had a job. The policy was based on the simply idea that whenever the private sector failed to produce enough jobs, the government would set in with to produce jobs to absorb the surplus workers. For the second time, the national government had a Choice. It could create a system that eliminated the need for welfare, and ensure that everyone had an opportunity to work. The government decided not to do this. When the Full Employment Act was passed in 1946, the bill had been gutted. Thus, when the Urban Age ended in 1950, blacks were still locked in obsolete, low-paying jobs at the bottom of the economy.

The Neoliberal Age [1950-2015]

Blacks have encountered novel challenges in each historical moment, which forces them to adapt and discover new methods of struggle. The Neoliberal Age was no different. Yet, at the same time, this era proved to be more complex and difficult than any other. It consists of two distinct periods. The first extended between 1950 and 1970, and the second from 1970 to the present. The twenty years, between 1950 and 1970 was the most turbulent in black history, and it was shaped by convergence of four interactive and overlapping forces of change: the Second Great Migration, rise of the metropolitan city, the radical transformation of the economy, and the Civil Rights Movement.

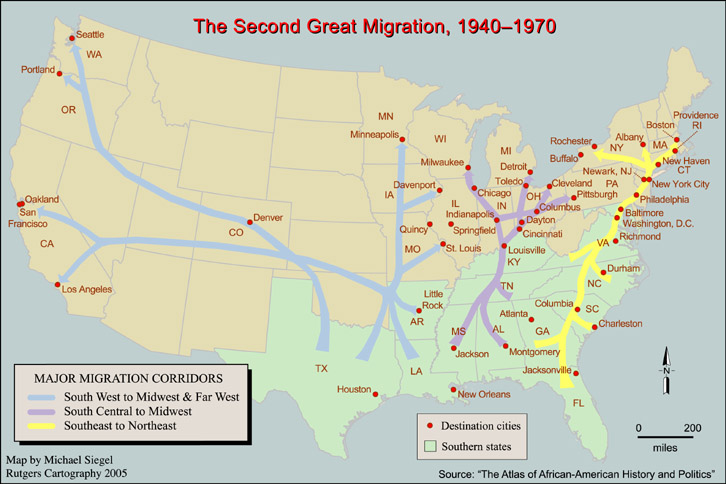

In 1954, at the very moment that blacks were celebrating passage of the 1954 Supreme Court decision and preparing for their final onslaught against the citadel of Jim Crow Racism, the powerful forces of socioeconomic change were starting to dramatically alter their world. In the years following World War 11, the economy shifted from industry to service, high technology and information and from Keynesian to neoliberal economic policies. This economic transformation also spawned, in part, the Second Great Migration between 1940 and 1970. This movement of thousands of blacks from farm to city altered the landscape of American cities and spawned the chronic urban crisis.

More than five million blacks moved to urban centers during this moment, which changed the dynamics of urban development. For example, the black population of Detroit jumped from 9% to 44%, Cleveland from10% to 39%, St. Louis from 13% to 41% and New York from 6% to 21%. In virtually every urban center in the country, the black population increased dramatically. As blacks moved in and even larger number of whites moved to the suburbs. In Detroit, the white population fell by 59%; in Cleveland, 50%; St. Louis 52%, and New York, 16%. The story of a socially transformed metropolitan region was the same everywhere.

Blacks entered cities undergoing massive change. As thousands of blacks poured into the urban centers, the federal bulldozer was displacing thousands as they remade the city by building roads and highways to connect with the suburbs and interstate highway system, expanding downtown, and hospitals, universities and cultural institutions. This process turned the central city and suburban municipalities into one big urban metropolis, which altered fundamentally the dynamics of black neighborhood and community development. What happened to blacks was now dependent on dynamics occurring across the urban metropolis, not just in the central city.

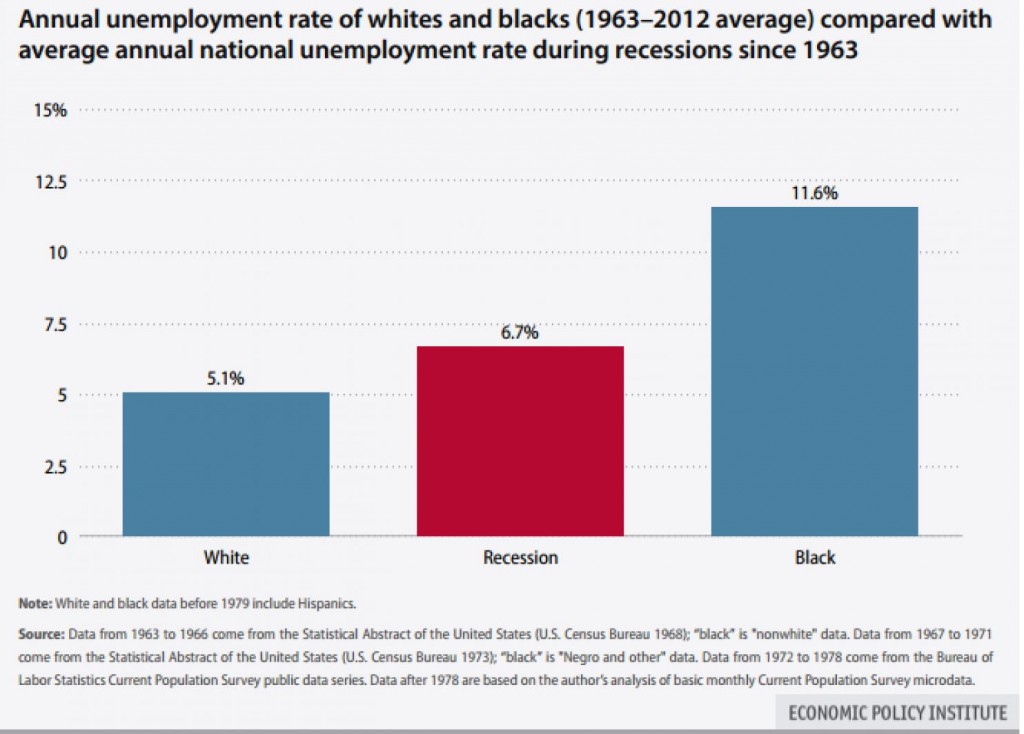

Hopeful blacks came to the cities searching for opportunities, but instead they encountered indifferent political leaders, racist police, underdevelopment of neighborhoods, and a changing economy. When blacks started their northern trek, for example, they had no idea that emergent neoliberalism was combining with a technological revolution to eliminate jobs almost as quickly as they got them. Robert Weaver knew this, but his quest for a Full Employment Act failed. Blacks were in deep trouble. Between 1953 and 1962, almost two million blue-collar jobs disappeared, and by the mid-1960s, blacks were experiencing double-digit unemployment, and some were leaving the labor force altogether. Commenting on the economic plight of black workers in the 1960s, the Civil Rights Activist Tom Kahn lamented, “It is as if racism, having put blacks in their economic place, stepped aside to watch technology destroy that place.”

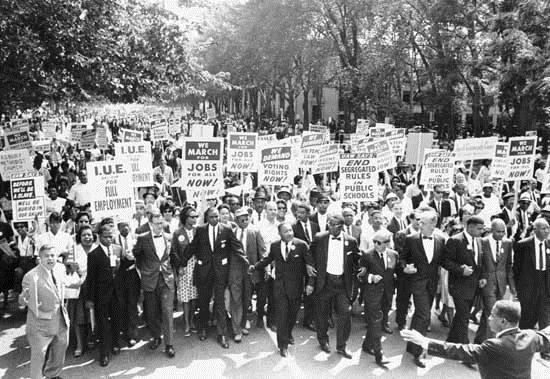

Flashing back to 1954, the Brown decision destroyed the legal foundation of Jim Crow Racism, and African Americans united to make their final onslaught against weakened system. That movement was launched on December 1, 1955, when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus to a white man, precipitating the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Over the next decade, blacks, and their white allies, waged a relentless struggle to win their civil rights. They engaged in mass organizing, built organizations, boycotted, marched, demonstrated, and protested; they held sit-ins, took freedom rides, conducted liberation classes, lobbied politicians, raised critical consciousness, and transformed their culture by reclaiming their identity—they discarded Negro, and called themselves black, adopted African names, embraced non-Christian religions, gave their children exotic, non-European names and reinterpreted their history. Then, with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of the 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 the citadel of Jim Crow Racism came tumbling down.

This dramatic victory on the Civil Rights front was both an epilogue and a prologue on the struggle of Black America. It ended the era when Civil Rights and the struggle for the smaller freedom dominated the black liberation agenda, while it simultaneously introduced the onset of a new era when the fight against neighborhood underdevelopment, joblessness, the inadequacy of education and other urban-based socioeconomic conditions would dominate the black liberation agenda. This struggle brought structural racism and thick injustice to the forefront. The Civil Rights battle removed facades that concealed the structures, policies, institutional and individual practices that restrict black access to the resources, opportunities and power required to develop their communities and move up the socioeconomic ladder. In this new setting, the emergence of Fair Housing legislation combined with the rhetoric of American being in a post-Civil Rights Age made the exploitation and oppression of blacks imperceptible.

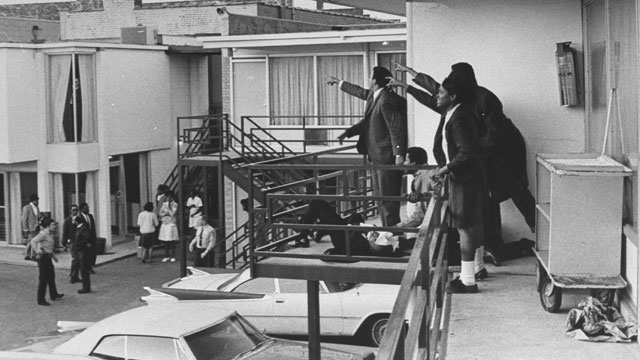

In the sixties, the stealth character of structural racism and thick injustice notwithstanding, the changing mood of the black masses and the evolution of new forms of struggle were evident. The 1964 Harlem Rebellion, the long hot summers of urban rebellions, emergence of the Black Power Movement, rise of the Black Panther Party, the Campus Revolution, emergence of the Anti-Revisionist Community Movement, and the advent of radical black, Latino, Asian and white organizations uniting to build a just society provide evidence of the emergence of a new movement. The assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. closed out the 1960s and formally ended the Civil Rights Age.

Neoliberalism Matures: 1970 -2015

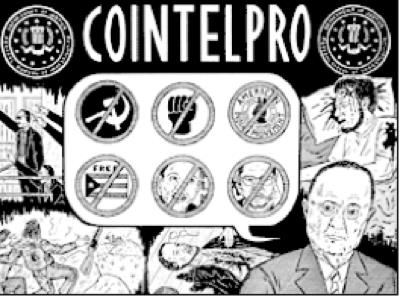

The seventies did not duplicate the turbulence of the 1960s, and it proved to be a transitional period. The maturing of neoliberalism combined with the brutal suppression of the radical left by the FBI’s Counter Intelligence Program [COINTELPRO] ushered in a new period in the long black struggle. During the seventies, the campus revolution transformed higher education, while blacks begin the complex task of building new organizations and institutions to tackle the more complex, structural problems facing the race. Concurrently, the repression of the radical black left intensified.

By the end of the decade, COINTELPRO and their allies had literally destroyed the radical black left, along with their white allies. With the radical movement in shambles, black middle-class optimism soared, while the conditions of the masses worsened. In this moment, the greatly expanded college educated elite pursued their careers, black entrepreneurs built their businesses, while black entertainers and professional athletes entered a Golden Age.

The quest to integrate into white society replaced the quest to build the black community, while lack radicalism was suppressed. Ironically, the building of elite black middle-class neighborhoods in the Washington, D.C., Atlanta, Georgia and the black suburbanization movement were part of what I call “black neoliberal integrationism.” This concept means the embrace capitalist cultural values, including the placement of individual goals over group goals, and the quest of professional advancement without a sense of black social responsibility.

The black middle-class believed that King’s Dream had come true. The election of Barak Obama as the first black president of the United States had people dancing in the streets, and soon, liberals and conservatives alike were declaring that America was now in a “Post Racial Age.”

This ideal of progress, of course, was an illusion. Between 1970 and 2013, black progress was essentially flat-lined in terms of the median household income, percentage of blacks in poverty, the white-to-black unemployment ratio, and the percentage of blacks attending segregated schools. Black incarceration, however, was not flat-lined. It grew exponentially over this time period, making the United States in the leading jailer in the world.

Meanwhile, the wealth gap between blacks and whites expanded dramatically between 1983 and 2010. Indeed, across the country, black homeowners were devastated by the subprime mortgage crisis, with many losing their homes or having their mortgages go underwater. Thus, the expansion of the college educated elite, along with the rise of Oprah Winfrey, Tiger Woods, Michael Jordan and the legion of pro football, basketball and baseball players could not keep the black-white wealth gap from widening, nor could they move the median household needle.

Ferguson shattered this black illusion—the myth suburbia as some type of mystical neo-Promised Land, where blacks could find freedom and opportunity. No one saw Ferguson coming. The shooting of Michael Brown on August 14, 2014 ran counter to the Black American Dream narrative. Blacks were told they could move to freedom. In retrospect, Fair Housing, Section 8, Affordable Housing, Moving to Opportunity, HOPE V1 and poverty deconcentration were all about “moving to freedom,” or that the life chances of people could be fundamentally altered simply by changing their addresses.

Ferguson terminated this fantasy. It demonstrated that black suburbanization actually represented the metropolitanization of the chronic urban crisis. The black urban predicament was no longer central city problem; it was now a metropolitan problem. Even in exclusively black middle-class neighborhoods the racist mortgage system wreaked havoc by robbing blacks of millions in home equity. In this new context, the epicenter of racism and social class inequality had shifted to underdeveloped black neighborhood. And it will be here that we find the next phase in the long black struggle for liberation.

Conclusion

In closing, I want to reflect on what we have learned from the long black struggle for freedom. To start, the black liberation movement will continue as long as blacks are denied access to the larger freedoms and find themselves the target of oppression and exploitation, police brutality, and structural racism and thick injustice. Blacks have always been unfree in the United States. This reality caused “struggle” to be interwoven into the fabric of black life and culture. However, while the black liberation struggle will be continuous and ongoing until they are free, the struggle will take different forms at different time. So, the struggle against the varied manifestations of structural racism and thick injustice will be different from the Civil Rights Movement, although it will certainly use some of the strategies and tactics.

Another critical lesson is the role that underdevelopment plays in the suppression of black America. At every stage, the brutal and systematic underdevelopment of blacks kept them tied to the bottom of the economy. This positionality of blacks at the bottom of the occupational structure, made possible their exploitation in other levels of society, it represents one of the cornerstones of structural racism and thick injustice. Here, it should be stressed that over time African Americans have battled against slavery, debt peonage, Jim Crow racism, and now structural racism and thick injustice, operating in the context of neoliberalism. In some respects, this struggle is the most complex ever faced by blacks. One reason is the struggle to free blacks will require a movement to transform the United States into a social democrat state. This will not happen overnight, but it will occur in a piecemeal, incremental fashion.

This brings me to the last point. Study of the long struggle indicates that blacks can and will win the battle for their liberation and freedom. For example, blacks and their allies defeated the slavocracy, and they defeated Jim Crow and state sponsored racism and discrimination. The battle against structural racism and thick injustice will also be won.

***

Henry Louis Taylor, PhD, is a Professor in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning and Director of the Center for Urban Studies at the University at Buffalo, New York. His research focuses on a historical and contemporary analysis of distressed urban neighborhoods, social isolation, and race and class issues among people of color, especially African Americans and Latinos.

Henry Louis Taylor, PhD, is a Professor in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning and Director of the Center for Urban Studies at the University at Buffalo, New York. His research focuses on a historical and contemporary analysis of distressed urban neighborhoods, social isolation, and race and class issues among people of color, especially African Americans and Latinos.